Markets or Governments?

Who should set the rules and incentives for responsible behavior in space?

By Michelle L.D. Hanlon

On December 11, I was honored to participate in a debate at the 20th Annual Eilene M. Galloway Symposium on Critical Issues in Space Law. I was asked to argue in favor of the resolution that: Markets (Not Governments) Should Set the Rules and Incentives for Responsible Use of Outer Space. These are my opening remarks. Many thanks to the organizing partners: the International Institute of Space Law, the Space Court Foundation, Akin Gump, Greenberg Traurig and the McGill Institute of Air and Space Law for creating a forum that invites serious, public engagement with the hardest questions in space governance.

These remarks were delivered in a debate setting and proceed from two important assumptions.

First, the question is not whether space should be governed. It already is. This argument assumes the continued force and relevance of existing international space law, including the Outer Space Treaty and its core principles.

Second, the resolution does not seek to dismantle or replace that legal framework. Rather, it asks a narrower—and more practical—question: once baseline rules exist, who is best positioned to shape the norms, standards, and incentives that guide responsible behavior as activity in space accelerates?

With those assumptions in place, the following makes that argument that markets, rather than governments, are better suited to write the next layer of rules—not in opposition to law, but in advance of its formal codification.

New Domains Write Their Own Rules

We are standing on the threshold of a new age of discovery—one with only a single close parallel in recorded human history.

This age is not about conquering other people. It is not about empire.

It is about discovering new resources and platforms to support human growth, resilience, and ultimately, expansion beyond Earth.

And that raises a difficult question: who should set the rules and incentives for responsible behavior in space?

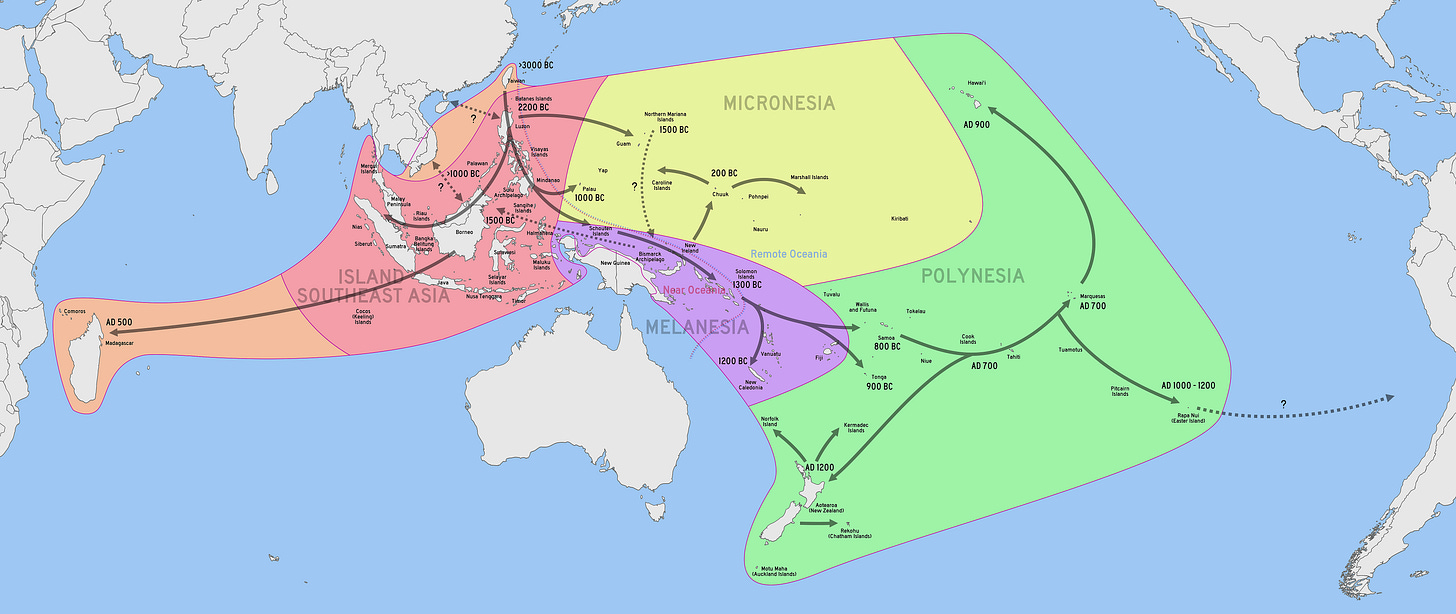

More than 2000 years ago, a group of humans on an island in the South Pacific looked across an idyllic beach at a vast ocean – an ocean so unblemished that it looked like you could sail right to the stars themselves. They had no idea what was beyond. Only that they felt a perhaps primal need to explore. A need possibly enhanced or exacerbated by crowding on their small island.

These were the Polynesians, the greatest navigators in history, a people that managed to spread themselves from modern day Indonesia, all the way to Chile.

Imagine trying to regulate the Polynesians.

Long before compasses or charts, they crossed the Pacific using stars, winds, swells and birds. No king, no council, no distant authority could have told them how to sail.

They created the rules of the ocean because they were the only ones who understood it.

And they weren’t alone.

Imagine trying to regulate the Vikings before Europe even grasped what the North Atlantic was.

This isn’t just a Polynesian or a Viking story — it’s the story of every frontier:

Early maritime law came from merchants, not monarchs.

Railroads standardized gauges, signals, and time zones before Congress ever acted.

Aviation pilots defined right-of-way and radio procedures long before ICAO.

The internet’s architecture was written by engineers not by national regulators.

Even global shipping containers were standardized by industry before governments noticed.

Across every era, the same pattern holds: the people at the front create the norms, and governments codify them later.

Operators – the doers – shape responsibility long before States understand the domain they’re trying to regulate.

This is space right now.

The Polynesians, the Vikings, the pilots, the railroad engineers, the internet architects — they all built responsible systems through practice, necessity, and cooperation, not decree.

The people who know the environment best write its first rulebook best.

And today, in space, those people are overwhelmingly commercial.

State-Based Lawmaking Cannot Keep Pace

More recent history offers us another important lesson. The last binding treaty seeking to address space activities was agreed in the 1970s. And that last Treaty found only 18 ratifications (now reduced to 17 with the withdrawal by Saudi Arabia).

History shows we cannot rely on the United Nations or any international State body to agree to new binding rules. While we must all applaud the efforts of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space – the Action Team on Lunar Activity Consultation (ATLAC) in particular holds great promise – the fact is that the international state mechanisms are slow. The purpose of the ATLAC is not to create a consultative body, but to decide whether a consultative body ought to be created, and if so, what issues that body should address. ATLAC will submit its recommendations to the UN in 2027.

It’s glacial. And humans are moving faster. The reality is, whether we like it or not, norms and standards are going to be shaped by the commercial entities in space and ultimately on the lunar surface. We see it happening already with Starlink’s collisions avoidance processes and protocols. SpaceX does not call the US government everytime there is a potential conjunction! Markets are already setting rules.

Markets Expand—Not Restrict—Participation

And this is a good thing. When governments set the rules, only states have a seat at the table—and usually only a few.

Markets open the door much wider to include: startups, universities, insurers, investors, satellite operators, lunar service providers and civil society (including heritage advocates).

Every contract, interface agreement, safety protocol, and transparency practice becomes a site of governance.

Treaties have a handful of seats. Markets have hundreds.

Responsibility Is the Rational Choice

Markets focus on what must be done. Governments often focus on how it will look.

Government action is distorted by geopolitics, commercial action is disciplined by physics and balance sheets.

States can afford to posture; companies cannot.

If a spacecraft fails, collides, or interferes, the consequences are immediate: lost customers, higher insurance premiums, reputational damage, and often mission failure.

Commercial actors therefore have uniquely aligned incentives for responsibility:

Debris mitigation is not a diplomatic gesture — it’s survival.

Data sharing isn’t magnanimous — it keeps insurance premiums down.

Transparency increases customer trust and lowers operational uncertainty.

Protecting heritage (even absent formal commitments) avoids brand-defining PR disasters.

This creates a system where responsibility isn’t an aspirational norm — it’s the cheapest, safest, and most efficient way to operate.

And here’s the critical part: new, smaller players can influence norms simply by being better operators. A well-run startup with excellent conjunction practices can move the industry faster than a multilateral working group.

Markets reward responsibility immediately.

Governments reward it eventually — if at all.

Markets Create Standards That Scale

Interoperability is not optional in space—it is foundational.

Docking interfaces, payload standards, data formats, and conjunction protocols are more likely to emerge from commercial necessity than treaty negotiations.

A nonstandard system does not dock. It does not communicate. It does not sell.

This is how shipping containers, aviation standards, and the internet evolved. Space is no different.

Markets Coordinate Across Borders Better Than States

States collaborate to the extent politics allow. Companies collaborate to the extent systems must function.

A single mission may involve suppliers, operators, and customers across multiple continents. Hardware does not care about sovereignty.

Diplomacy gets stuck on language and sovereignty.

Markets get unstuck because the hardware doesn’t care about either.

Where states see risk, companies see throughput.

Where states see rivals, companies see customers and partners.Commercial coordination already outpaces state-to-state processes—because failure is not an option.

Efficiency Drives Responsibility

The market’s push for efficiency produces the hallmarks of responsible behavior:

Standardization. Transparency. Data sharing. Reliability.

The cheapest way to operate in space is also the most responsible way to operate in space.

The First Chapter Belongs to the Navigators

When the Polynesians launched their canoes, they did not know the ocean’s boundaries. They discovered them—and in doing so, they created an unwritten code for survival.

We are doing the same thing in space.

The first rules should not come from conference rooms. They should come from those who experience the domain as it truly is—vast, dynamic, and unforgiving.

The commercial explorers of our time are already writing the norms of responsible behavior through cooperation, transparency, and necessity.

One day, governments will codify those norms.

But the first chapter — as in every age of exploration — belongs to the navigators.

And in this new ocean above us, the navigators are commercial.

What do you think?